Collective Mining: How To Build A Billion Dollar Company By Illegally Drilling On Untitled Land

Background

- Collective Mining (TSX: CNL, NYSE: CNL) is a C$1.1 billion ($807-million) Canadian mining company focused on developing mineral deposits in Colombia.

- In June 2022, Collective announced “a significant new discovery,” a gold deposit known as the Apollo target. The discovery has led to a 285% rally in Collective’s share price, and the Apollo target now represents an estimated 93% of Collective’s net asset value, per brokerage estimates.

Conducting Exploration Activities Without A Mining Title

- Mining companies are required to obtain a mining concession agreement with the Colombian state to conduct exploration and mining activities in a specific zone, according to the Colombian mining regulator, the Agencia Nacional de Minería (“ANM”). These mining concession agreements result in the granting of a “titulo minero” (mining title).

- Collective claims that it is conducting exploration activities under “validly granted” mining titles, but our investigation reveals that a significant portion of the company’s activities are occurring on untitled land, including much of the drilling for its flagship Apollo target.

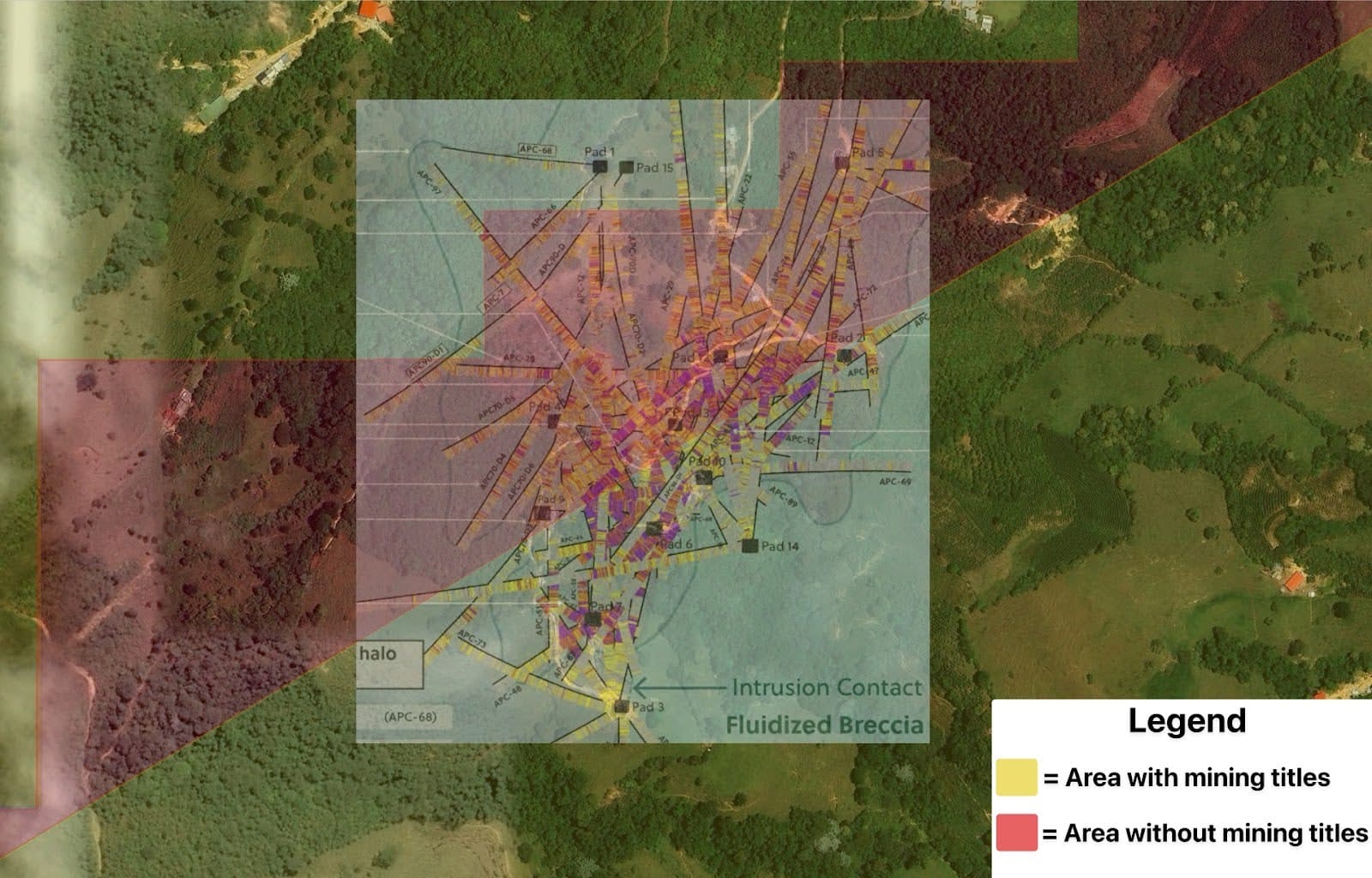

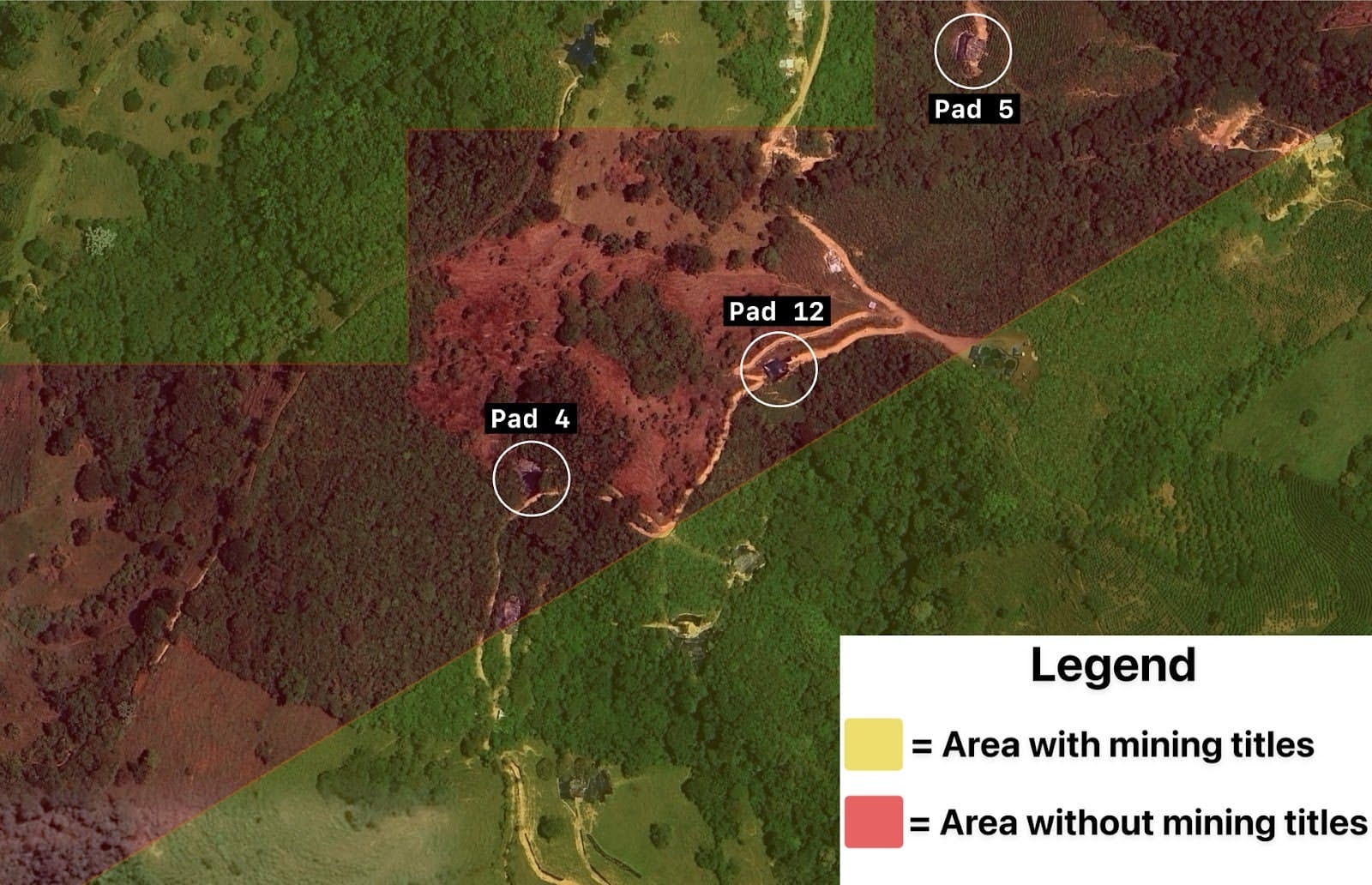

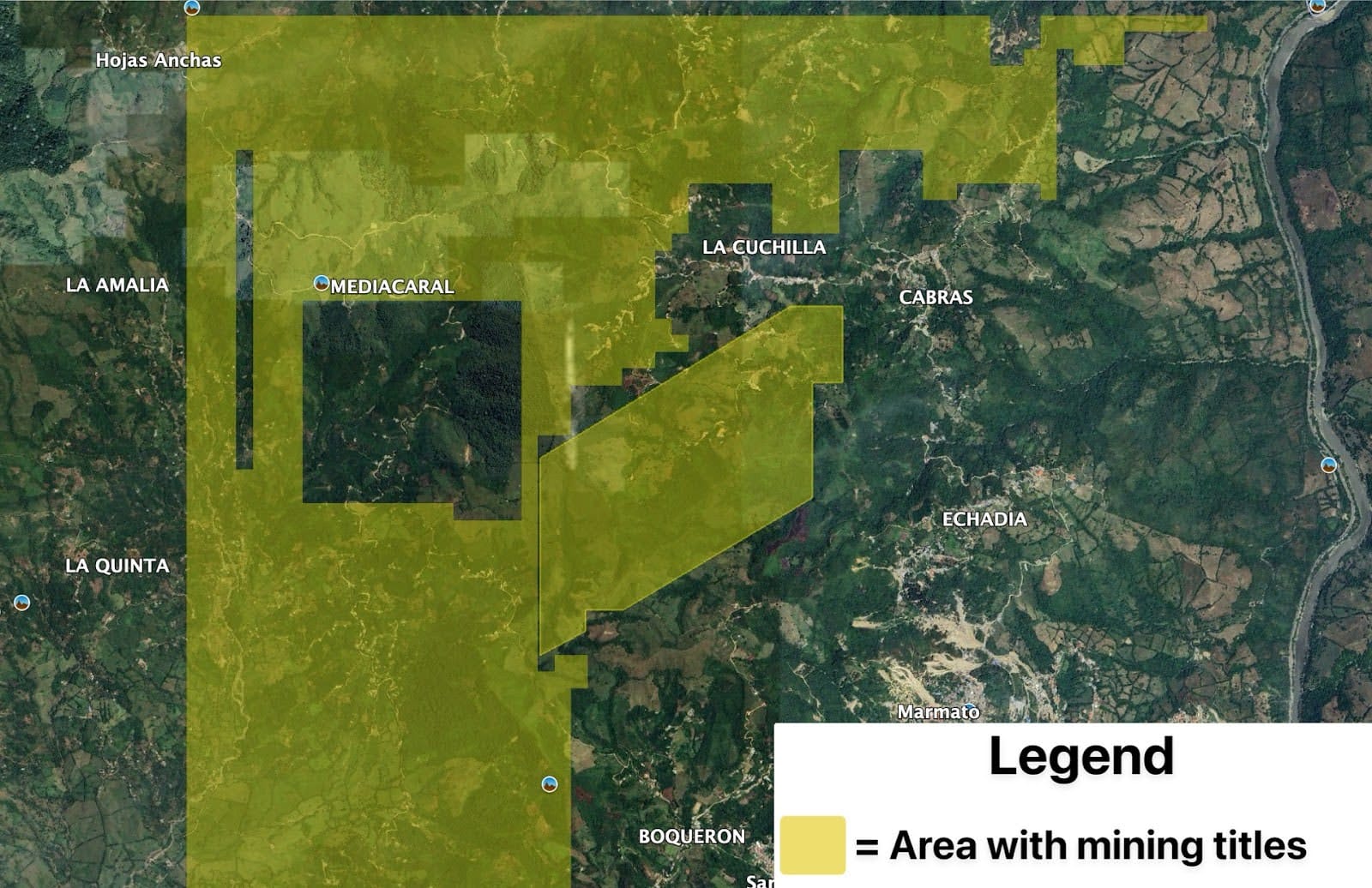

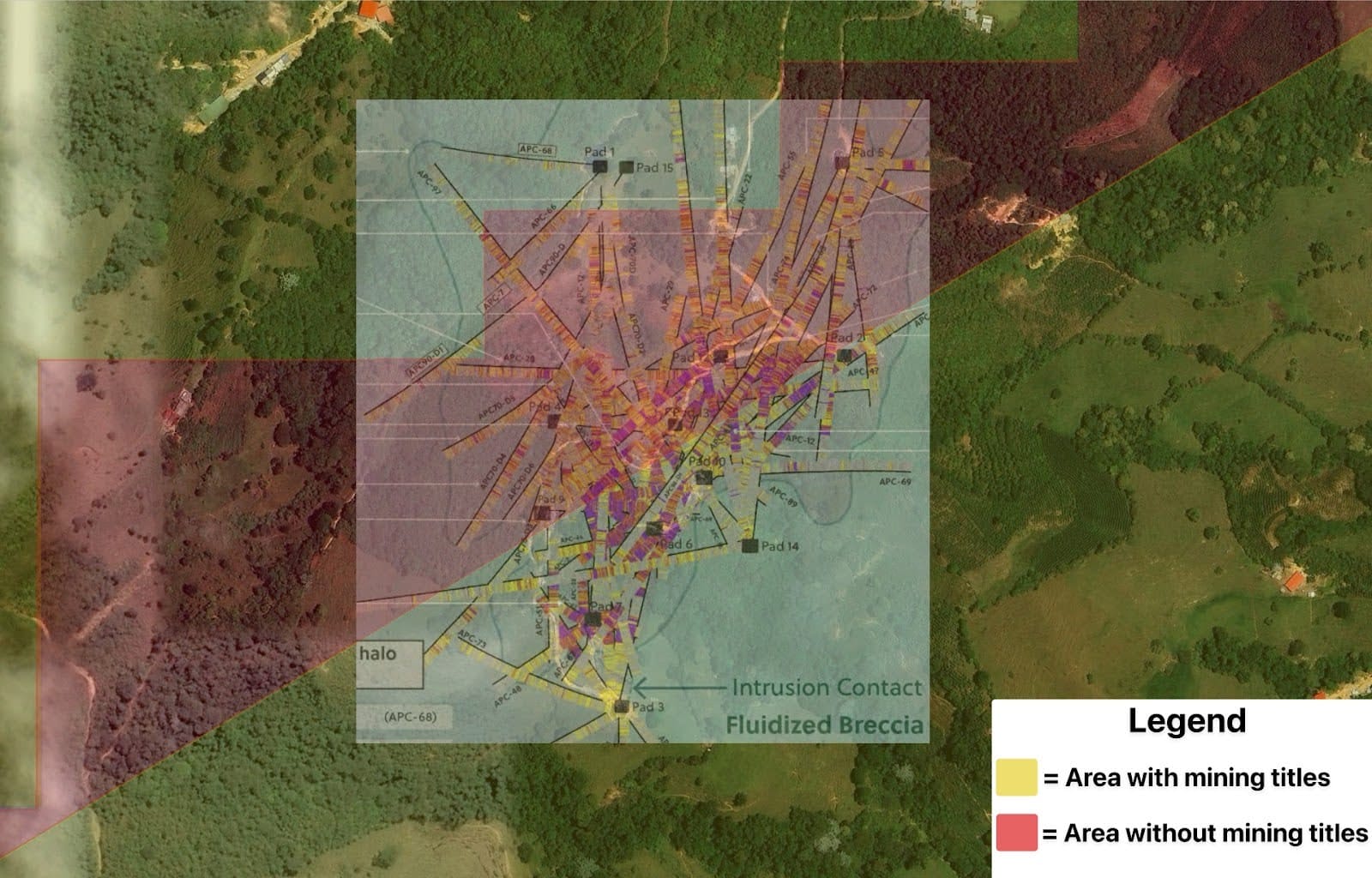

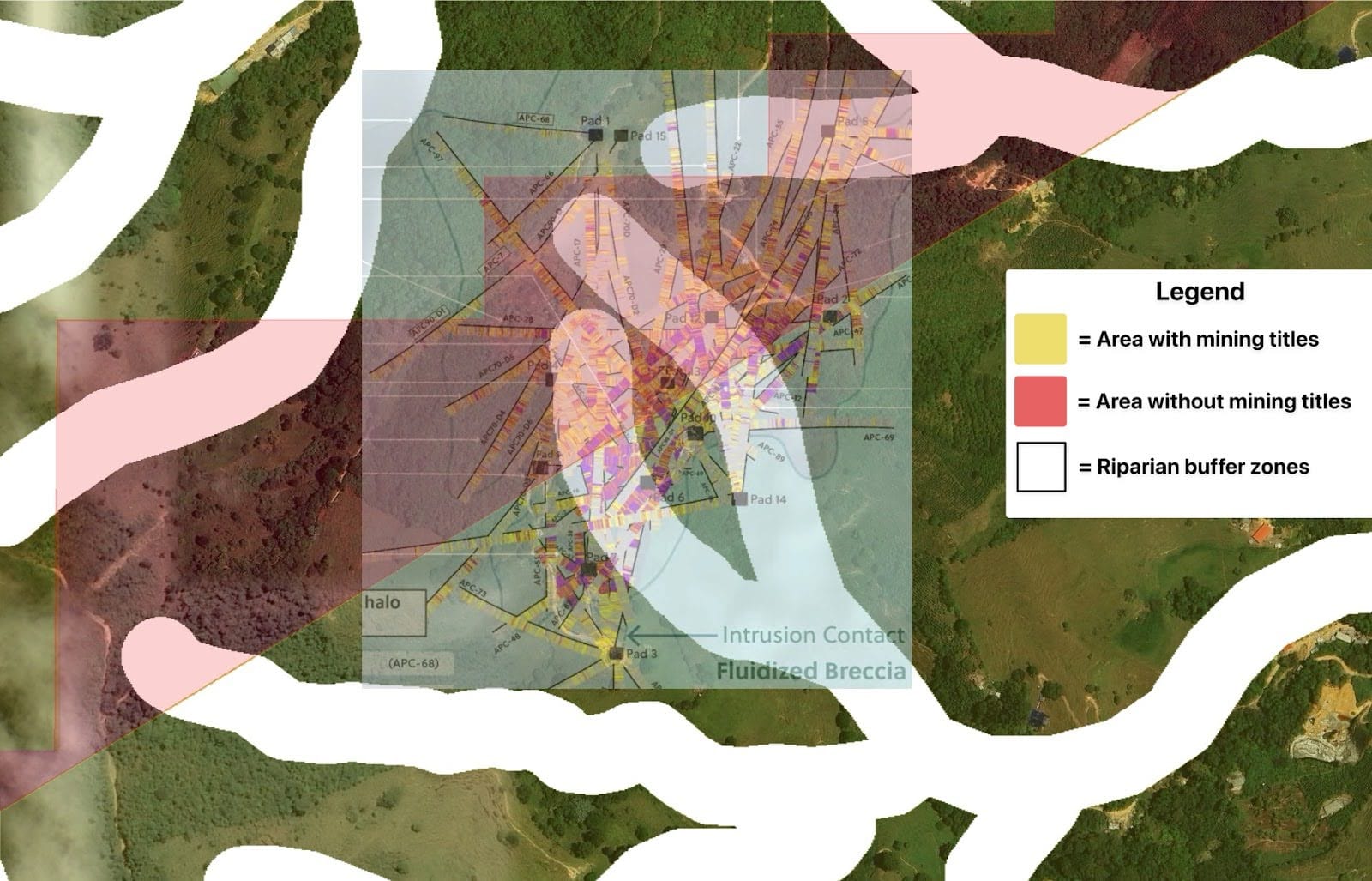

- By combining data from Collective’s technical reports and presentations with the ANM’s title database and superimposing that data onto satellite imagery, we were able to see that the bulk of exploration activities for the flagship Apollo target is occurring on untitled land.

- Collective is not just drilling into untitled areas from drill pads located on titled land at its Apollo target — 3 of its drill pads appear to have been constructed entirely on untitled land, according to our analysis of ANM titles, satellite imagery and Collective’s disclosures.

- Mining activities on untitled land and outside project boundaries have been met with swift and strict enforcement from the Colombian government. For example, in 2022, two separate companies operating in Colombia, Fura Gems and Minerandes de Colombia, were ordered to cease activities after they were discovered to have operated outside of the boundaries of their concessions, according to local media reports and the ANM.

- When asked about operating on untitled land, the CEO of a local mining consultancy firm told us: “There are very, very hard felonies for doing that. Because when you do that, the police arrive to your place and take prisoners of all [your] workers and they burn the [mining] machinery. In this place, it's very punished here in Colombia, because illegal groups, they used to profit from this illegal mining. So it's almost like a homeland security issue.”

Conducting Exploration Activities In Environmentally Restricted Areas

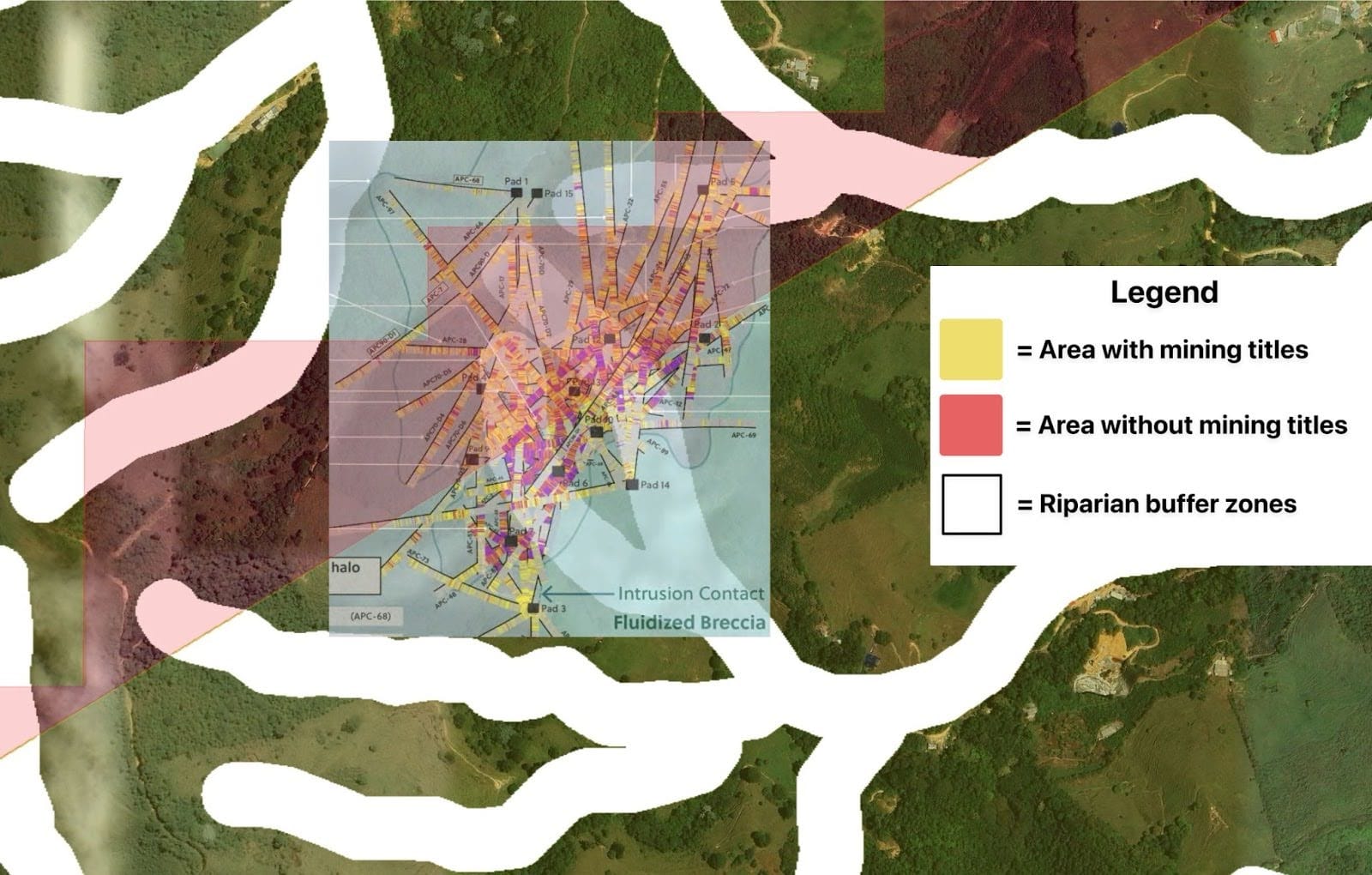

- Adding to Collective’s risk, drilling at its Apollo target also appears to occur on or near “riparian forest buffers,” based on Collective’s own drilling maps combined with data from Corpocaldas, the regional environmental authority. Riparian forest buffers are environmentally-protected areas where mining activities are restricted.

- In July 2025, two of Collective’s concession applications, outside the Apollo target area, were suspended by the ANM due to environmental concerns. The ANM orders state that the requested areas overlap with environmentally protected zones where mining activities are restricted, and suspended Collective’s application process until the company can show that its proposed mining activities are compatible with the environmental restrictions.

The Undisclosed Background Of Chairman Ari Sussman

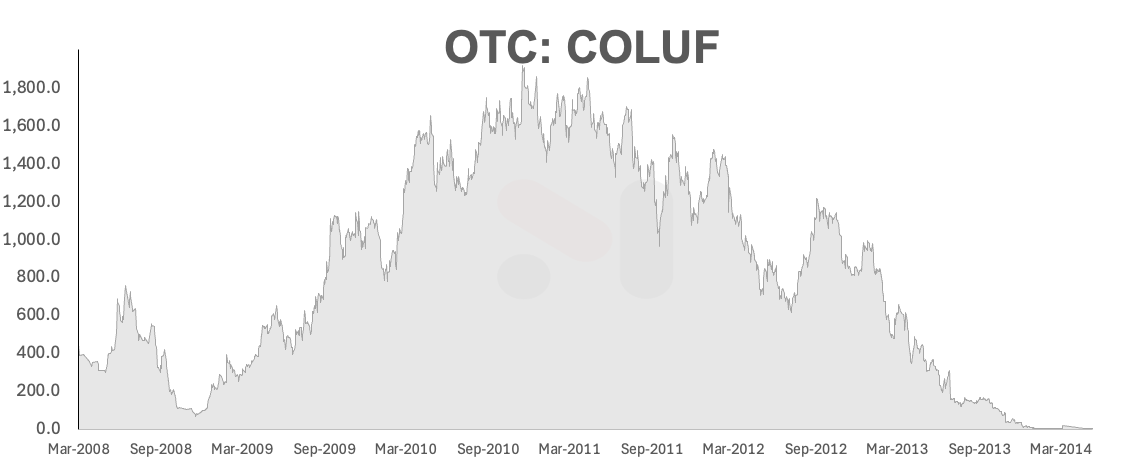

- Collective’s filings make little reference to its Chairman Ari Sussman’s past at Colossus Minerals in Brazil. He previously founded and led Colossus from 2006 - 2012. During that period, Colossus was accused of depositing the equivalent of $11.7 million into the personal bank account of an official from a local mining cooperative, per local media.

- In 2014, Brazil’s Congress cancelled Colossus’ mining license, with one representative saying, “The entire process, from the outset, was riddled with irregularities, corruption, and disregard for our country’s laws.” That same year, Colossus filed for creditor protection.

- Collective appears to be conducting the bulk of the exploration activities for its Apollo target on untitled land, which is strictly prohibited in Colombia. We believe this seemingly brazen disregard for Colombian law risks jeopardizing the future of its flagship mining target.

Initial Disclosure: After extensive research, we believe the evidence justifies a short position in shares of Collective Mining Ltd. (TSX and NYSE American: CNL). Morpheus Research holds short positions in CNL. This report represents our opinion, and we encourage all readers to do their own due diligence. Please see our full disclaimer at the bottom of the report.

Background: A C$1.1-Billion Exploration Stage Colombian Gold Mining Company

Collective Mining Ltd. (TSX: CNL, NYSE: CNL) is a C$1.1-billion Canadian mining company focused on exploring mineral deposits in Colombia.

The company was founded by Canadian executive and current Chairman Ari Sussman, who frequently provides updates about the company on social media.

Sussman has a history of operating mining companies in Latin America, including Continental Gold, which developed Colombia’s largest gold mine and was sold in 2020 for over $1.4 billion.

After selling Continental, Sussman’s team decided to “go back to Colombia” to “do it again” by founding Collective Mining, per Sussman’s interview with Proactive Investors.

In May 2021, Collective went public on the Toronto Stock Exchange by way of a reverse merger. Three years later, the company began trading on the NYSE American Exchange.[1]

The shell that Collective merged into, POCML 5 Ltd, was controlled by Pasquale “Pat” DiCapo of PowerOne Capital Markets Ltd, who as of May 2025 held 10.9% of Collective shares, according to Collective’s filings. DiCapo has invested in Colombian gold mining in the past with Tolima Gold and is a frequent partner with the controversial Andy DeFrancesco. ↩︎

Collective is pre-revenue and has “one material exploration project” called the Guayabales Project, per a March 2025 filing. This project is located in the Caldas region of western Colombia, historically known for gold mining.

Bull Case: Collective’s Apollo Target Is An Untapped Mining Opportunity With Potential Production Of 10 Million Ounces Of Gold, Representing ~93% Of The Company’s Net Asset Value, Per Brokerage Estimates

Colombia is a mineral-rich country that remains under-explored with less than 3% of its territory under title for mining and exploration, per industry consultancy firm, Ax Legal.

Collective’s Guayabales project is next to Marmato, a gold mining site that has been mined continuously for over 500 years and has produced between 1 million and 2.4 million ounces of gold, per brokerage firm Roth Capital.

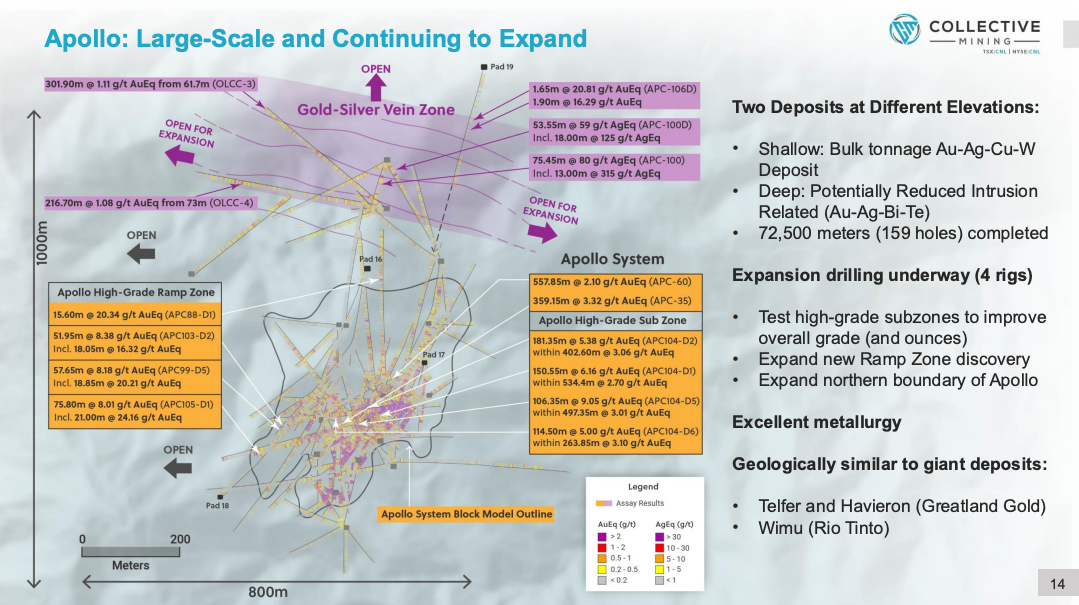

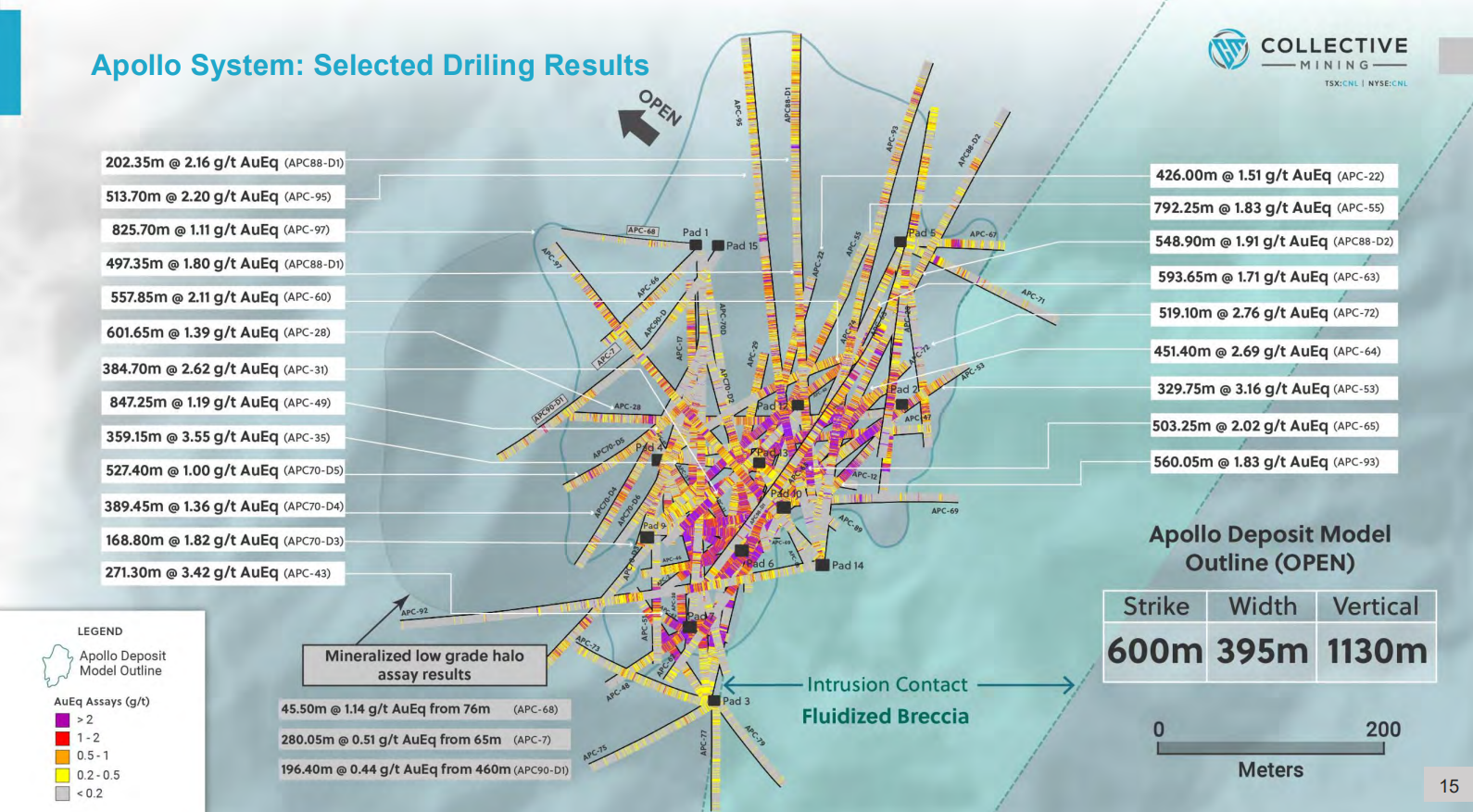

In June 2022, Collective announced “a significant new discovery” of a deposit consisting of gold, silver and copper, referred to as its “Apollo target.” As of June 2025, ~69% of the company’s drilling activity at Guayabales has focused on this target, per the company's press release.

The company has told investors of its “lofty goal” to find “over 10 million ounces of gold,” per Chairman Sussman. Some sell-side analysts predict the resource could be even larger at 15 million ounces.[1]

Roth Capital report dated June 9, 2025. ↩︎

Collective’s market valuation is based largely on the Apollo project, with analysts like Cannacord Genuity estimating that the project represents 93.4% of Collective’s net asset value.[1]

Cannacord Genuity report dated April 4, 2025 ↩︎

Since the Apollo discovery, Collective’s share price has rallied 285% as investors believe Sussman will replicate Continental Gold’s success. The company now boasts many large institutional investors like Jupiter, Franklin Templeton and Schroders, per Bloomberg.

Part 1: Collective Appears To Be Conducting Illegal Exploration Activities At Its Flagship Apollo Target

Background: Colombian Mining Companies Require A Mining Title To Operate In A Specific Area

Performing Mining Activities In Areas Without A Title Is Illegal In Colombia

Under Colombia’s constitution, the State owns all mineral deposits in the country with limited exceptions.

Mining companies are required to sign a mining concession agreement with the Colombian state to conduct exploration and mining activities in a specific zone, according to the Colombian mining regulator, the Agencia Nacional de Minería (“ANM”).

These mining concession agreements result in a “titulo minero” (mining title) which represents the right to mine in a property owned by the Colombian state, according to the Colombian Ministry of Mines and Energy.[1]

The ANM is responsible for overseeing and granting mining titles, which are usually given for a 30-year period with three different phases: exploration, construction and mining. [Pg. 2]

Mining without a mining title is expressly illegal in Colombia, as laid out by statute. We asked a CEO of a mining consultancy firm in Colombia about the legality of mining without a title, and the consequences of doing so:

“You can't. That’s called illegal mining … There are very, very hard felonies for doing that. Because when you do that, the police arrive to your place and take prisoners of all [your] workers and they burn the [mining] machinery. In this place, it's very punished here in Colombia, because illegal groups, they used to profit from this illegal mining. So it's almost like a homeland security issue.”

Collective Claims That It Is “Conducting Exploration Activities On … Validly Granted Mining Titles”

Reality Check: Collective Appears To Be Conducting Illegal Exploration Activities Beyond The Boundaries Of Its Key Mining Titles, Based On Data From The ANM

As mentioned, Collective’s focus has been its Guayabales project, specifically its Apollo target, according to the company’s 2024 annual information form.

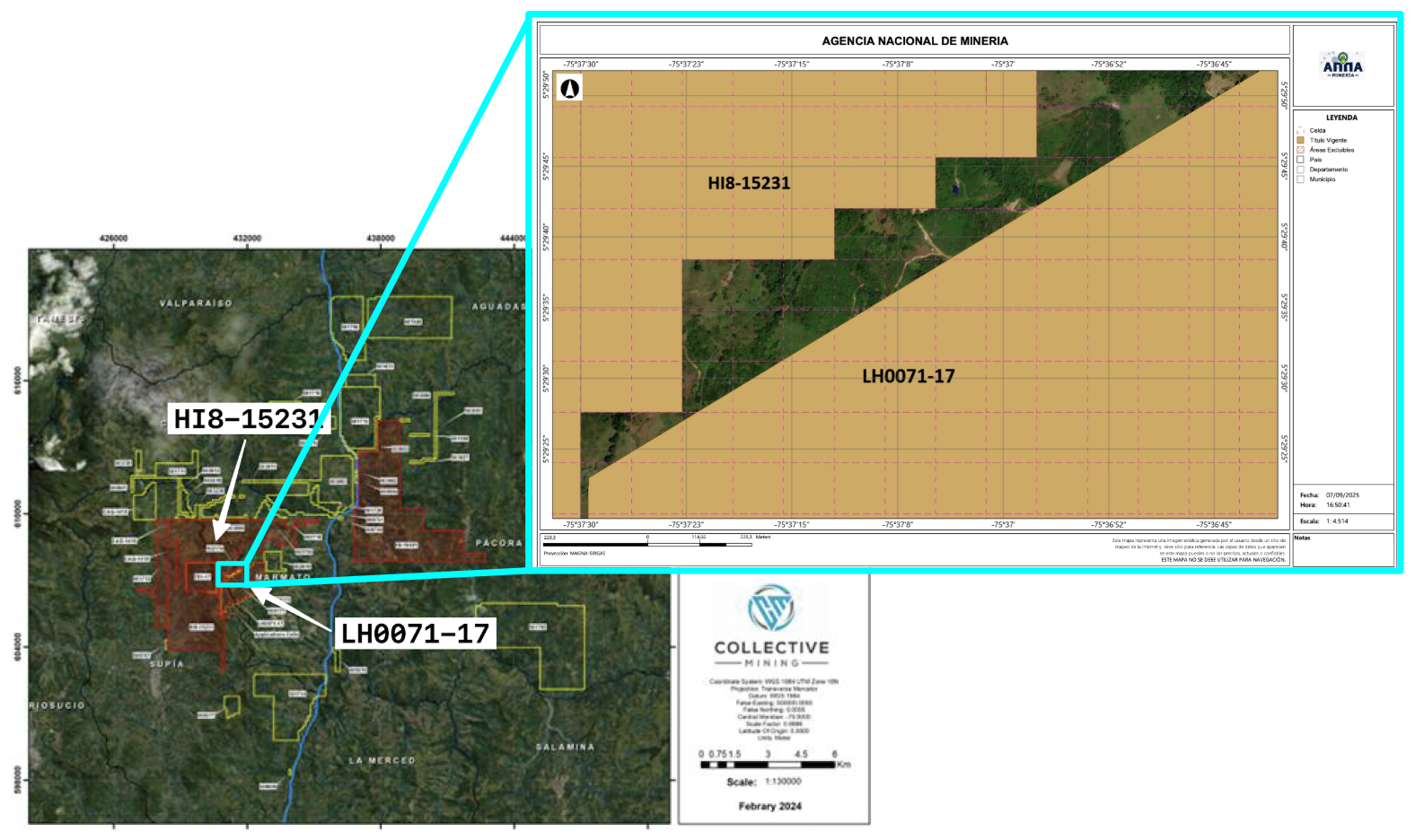

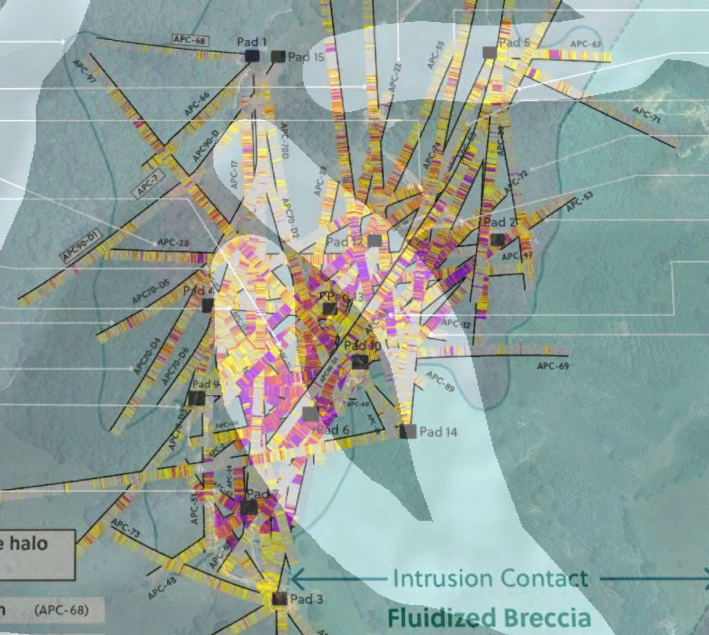

The Guayabales project comprises 4 mining titles, per the same document. The Apollo target straddles two of these mining titles at the Guayabales site. These are denoted by the title numbers “LH0071-17” and “HI8-15231.”[1]

The company stated in its latest annual information form that these titles are “validly granted mining titles.”[1]

Collective does not own the mining title LH0071-17, but has the option to acquire it, according to company filings. On June 23, 2025, the company announced that it was accelerating “its agreement with the vendor” of the Guayabales license. ↩︎

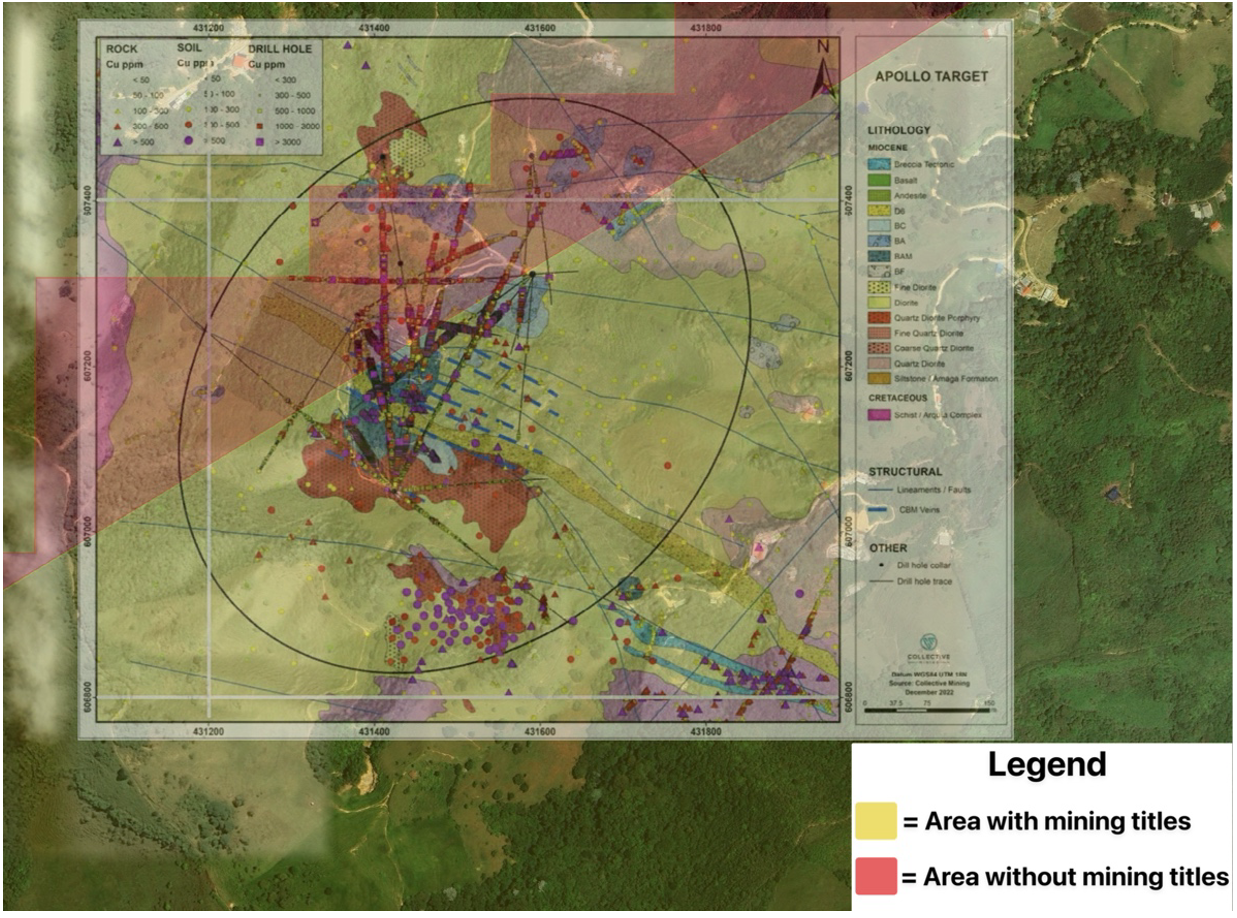

The ANM’s mining title database shows, however, that there is a key portion of land between these two titles that Collective does not hold the titles to, meaning any exploration or drilling activities in those areas would be illegal.

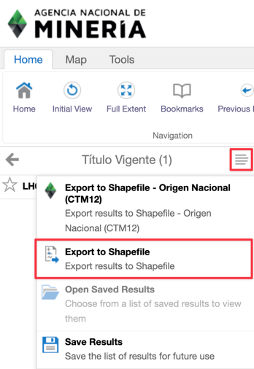

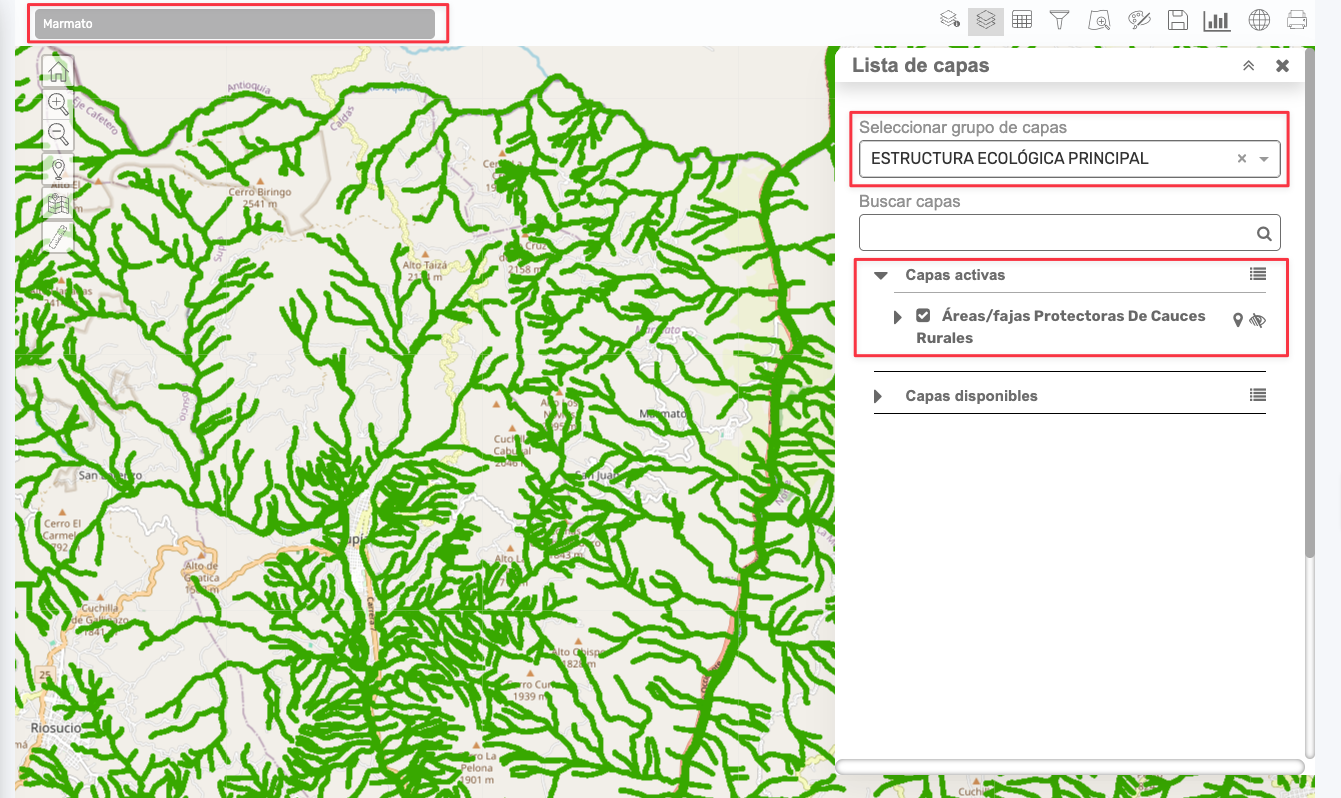

As seen in the image below, the area with mining titles is denoted by the gold sections, according to the ANM’s legend. This means that the clear area between the two titles does not have a mining title that allows mining activities.[1]

In 2019 Agencia Nacional de Mineria, abandoned the practice of granting a title based on irregular geometry and adopted a mining title standard based on a grid (a continuous set of cells of approximately 1.24 hectares each), according to a press release issued by the agency. ↩︎

Our research indicates Collective is conducting a significant portion of its exploration activities on the untitled land between its two titled areas.

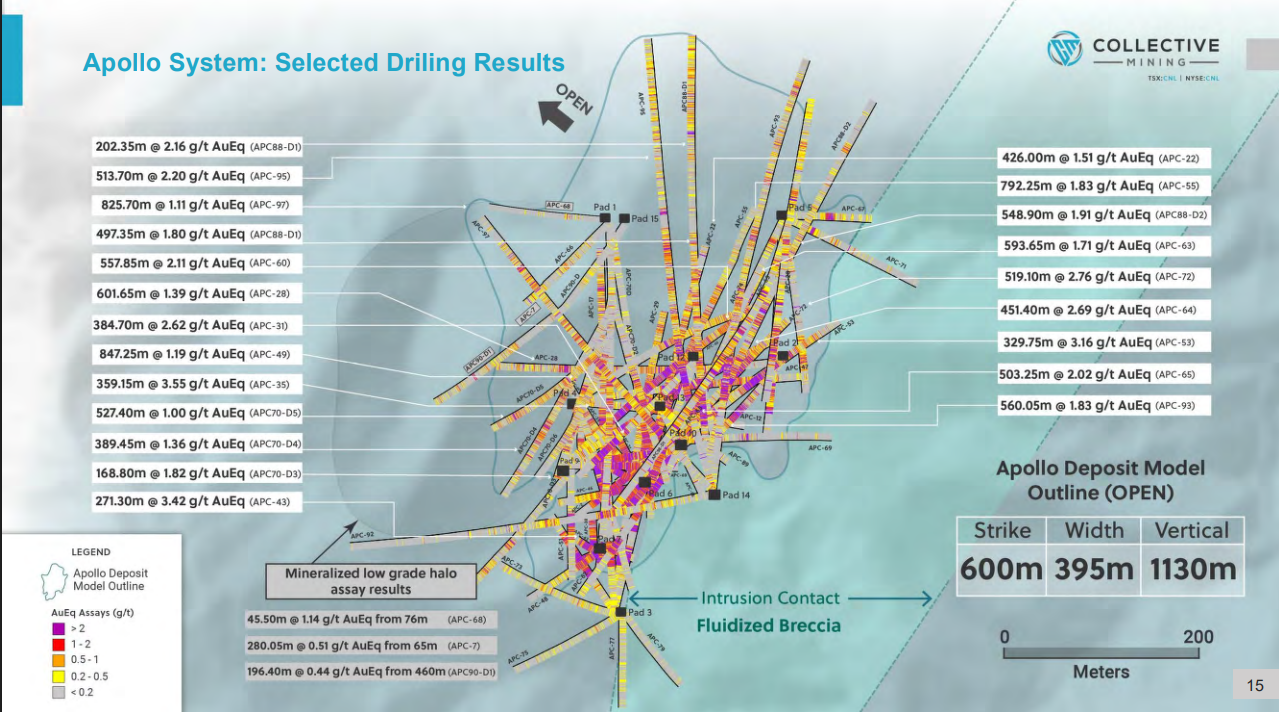

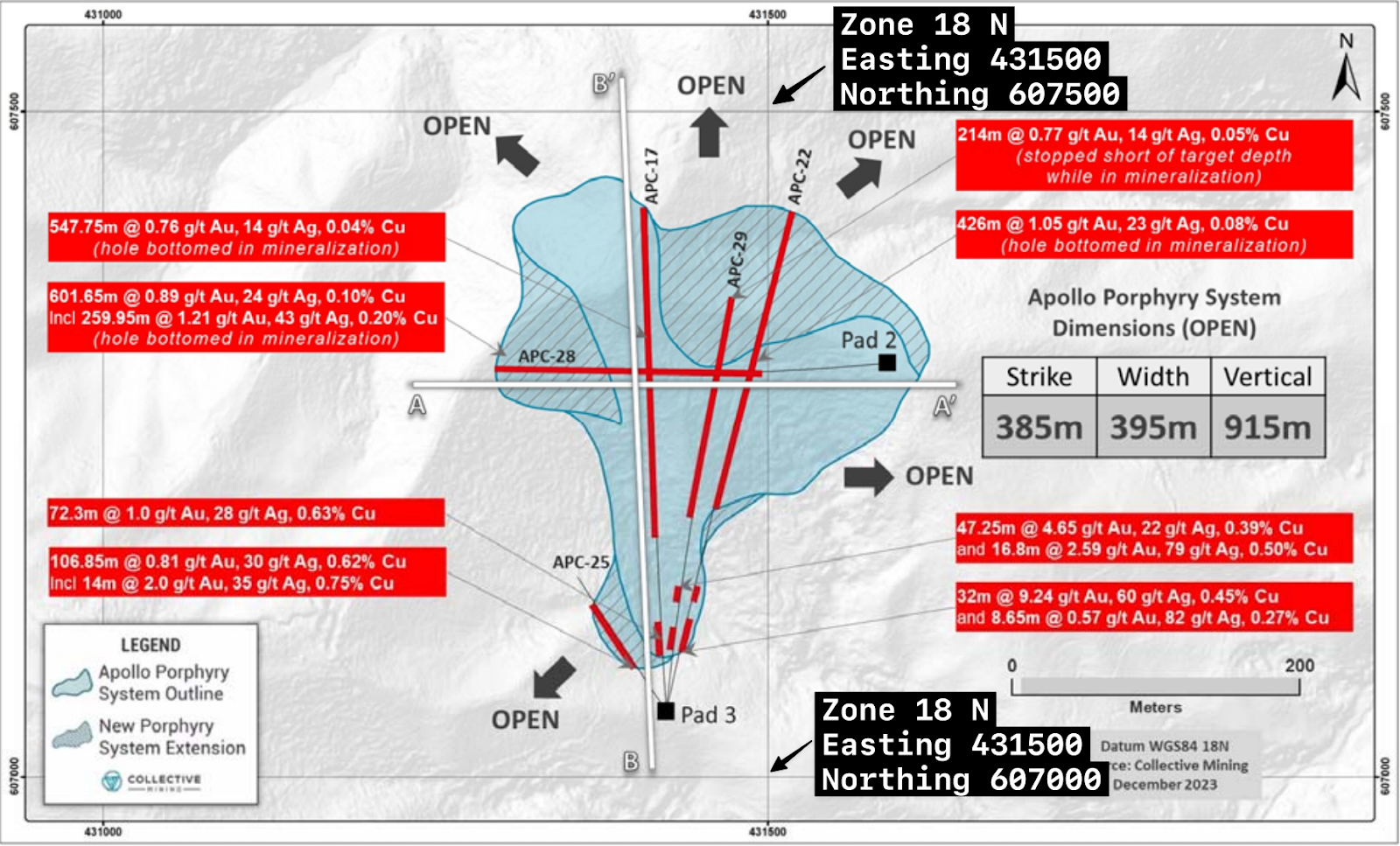

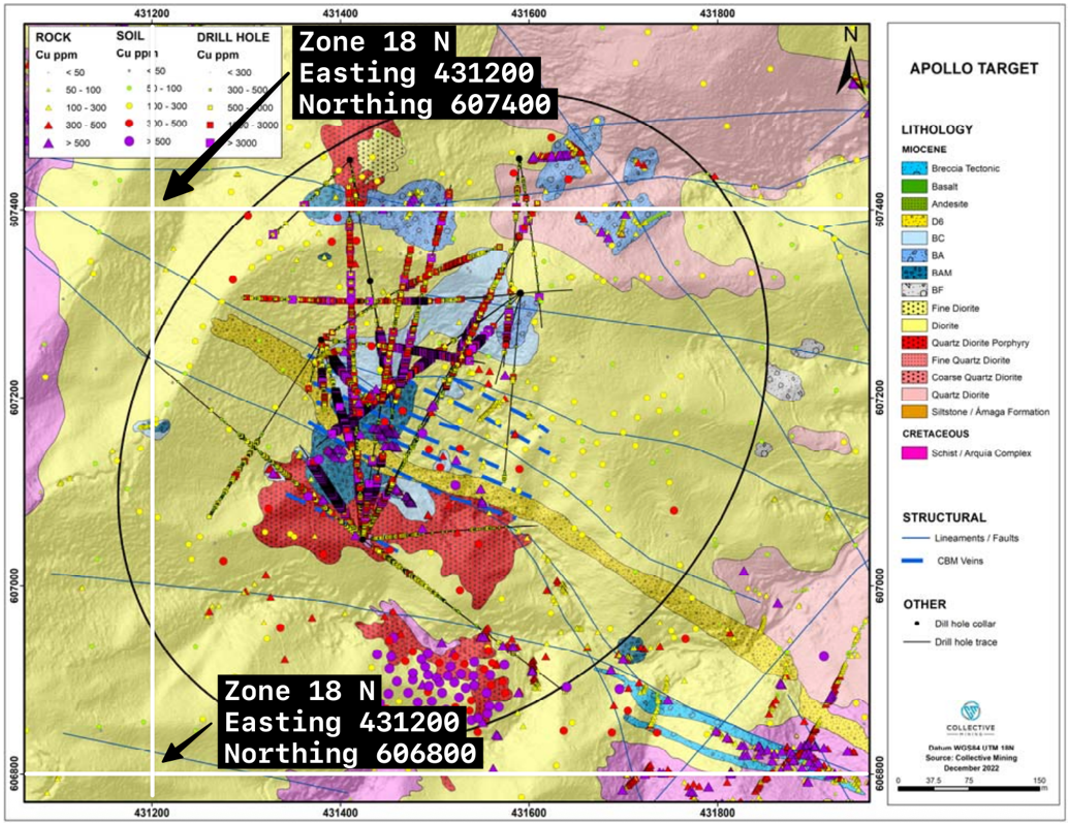

Using UTM coordinates from drill maps in Collective’s April 2023 technical report, we were able to locate specific drill pads (the base for drilling activity) and holes located within the Apollo target.

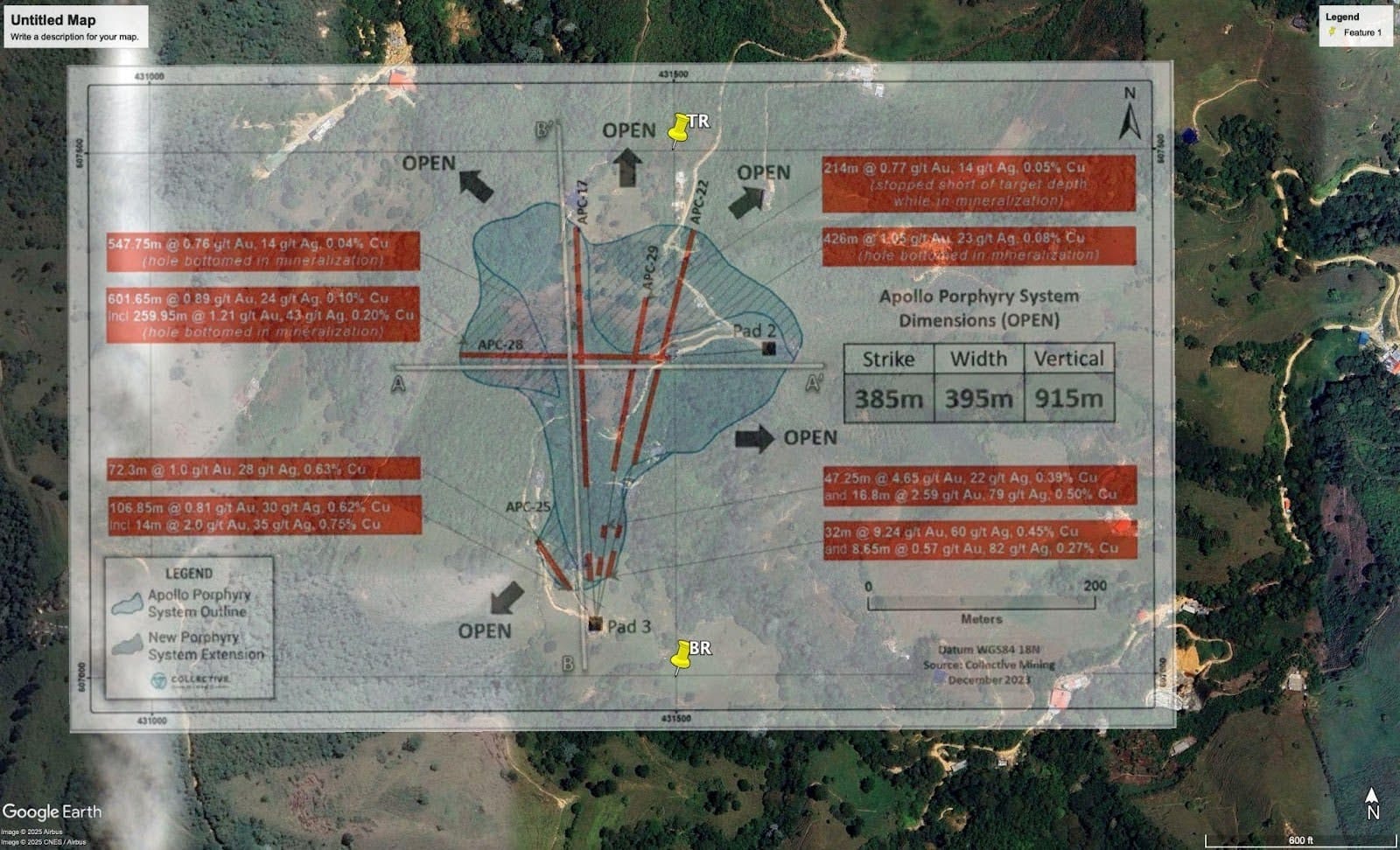

As detailed in Appendix A, our methodology used maps published by Collective Mining, the ANM’s mining titles database and Google Earth Pro. [Pg. 135] [Pg. 15]

This allowed us to determine that Collective is likely drilling in areas where it does not hold a mining title.

The image below features Collective’s drill holes associated with its Apollo exploration activities, clearly showing that a significant portion of them run through untitled land.

In its latest annual information form, Collective Mining states that it has 116 claim applications for incomplete cells surrounding “the two exploitation claims” of its Guayabales Project.[1]

According to Collective’s latest annual information form, incomplete cells “are gaps between claims that are smaller than the cell size that resulted from converting old irregular claim shapes to claims built of square cells.” Mining titles for incomplete cells can only be requested by the holders of the mining titles that intercept these cells, according to a local mining legal expert we consulted. ↩︎

Moreover, Collective has also submitted applications for mining concessions on specific areas where it appears to have drilled, according to the ANM’s database and Collective’s disclosures.[1]

We spoke to an industry expert and former executive at a Colombian mining company. We asked if drilling and exploration activities were allowed in an area while it was under an application. They said:

“No. Exploration activities can only be carried out when you have already signed a concession contract.”

Furthermore, we spoke to a current employee at Aris Mining, a mining company that operates the Marmato gold mine in Colombia next to Collective’s site, they told us:

“You always have to stay within the boundaries of your title. And going outside those boundaries can bring significant penalties. It would be considered illegal mining.”

It appears that much of the company’s drilling activity at its Apollo target has been conducted in areas for which mining titles have not yet been granted – implying illegal mining activities.[1]

As of this writing, the ANM has not published the approval of any outstanding mining title applications for Collective Mining on its website. They also have not updated the permited mining boundaries of any existing Collective title and no outstanding title applcations have been granted according to the online ANM mapping application. ↩︎

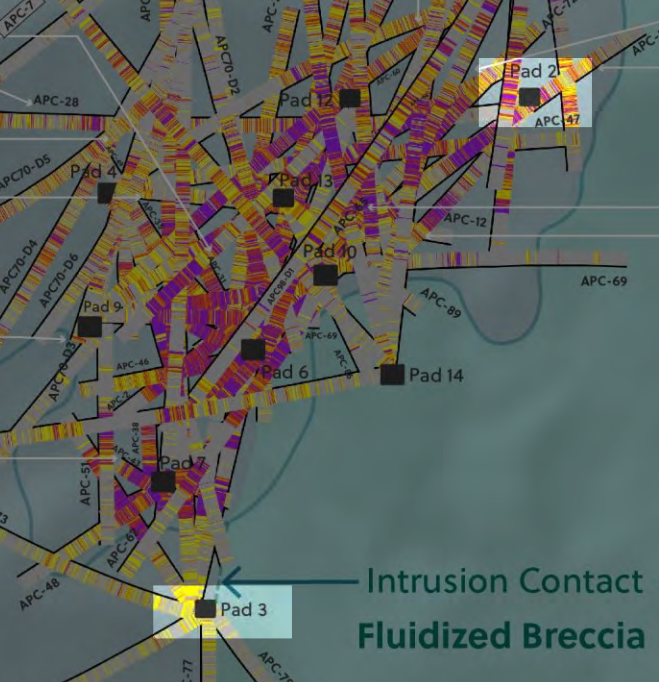

Collective Is Not Just Drilling Into Untitled Areas Below The Surface

Since At Least 2023, Collective Appears To Have Been Drilling From 3 Drill Pads Located Directly On Untitled Land, According To Company Disclosures And Data From The ANM

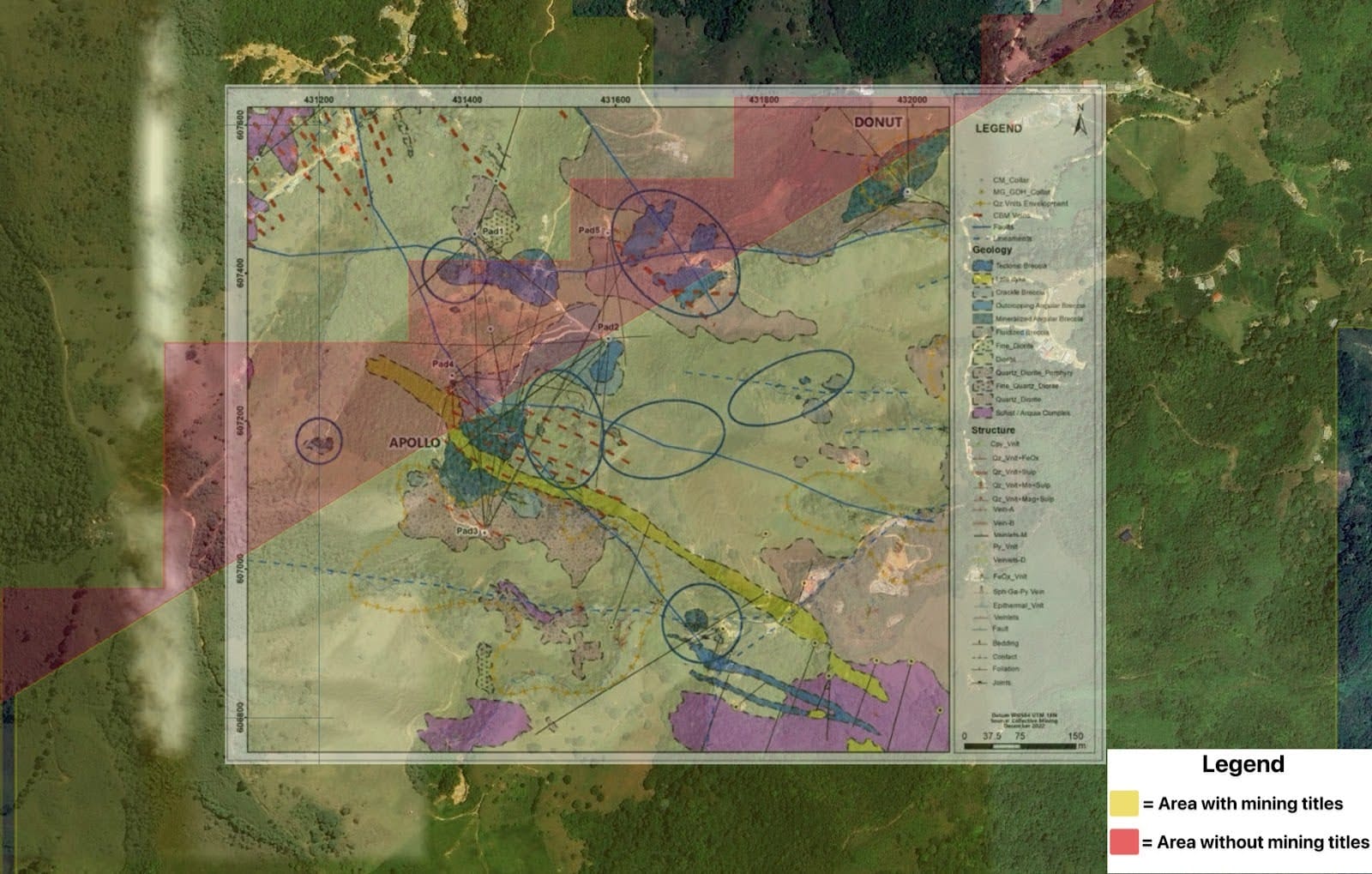

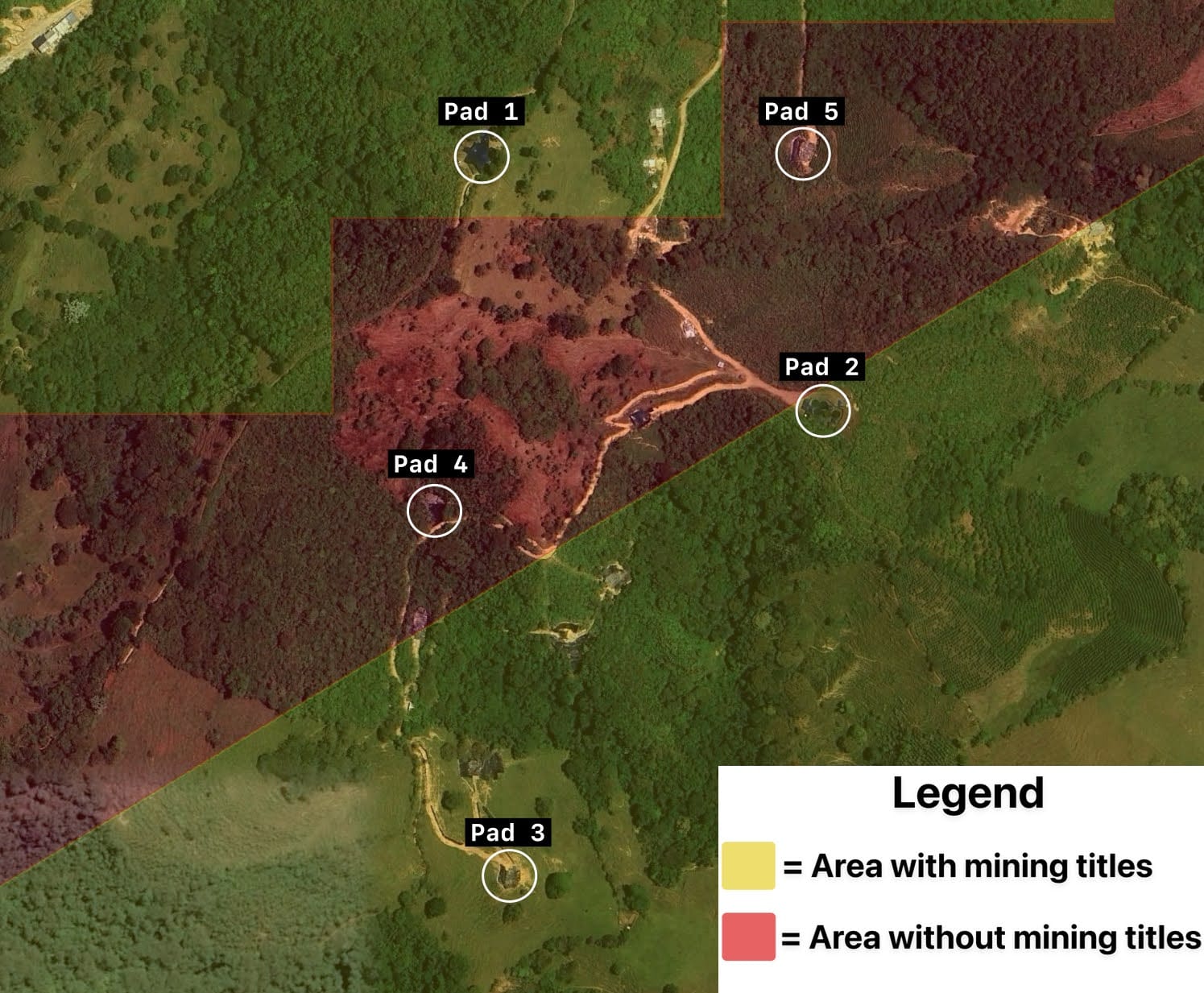

Collective is not only drilling beyond the boundaries of its titles, it has also installed drill pads directly on untitled land.

Since at least 2023, Collective has been drilling holes from Pad 4, Pad 5, and Pad 12, according to press releases issued by the company. Using the methodology described in Appendix A, we were able to identify the locations of Pad 4, Pad 5 and Pad 12.

Mining On Untitled Land Has Led To The Shutdown Of Projects By The Colombian Government

While illegal mining activity has been a long-standing issue in Colombia, much of this has been a result of criminal and rebel gangs rather than public corporations.[1]

The ANM has, however, stepped in to suspend activities by corporations mining illegally and outside of permitted boundaries or where there are specific environmental or technical non-compliances.

For example, in May 2022, Fura Gems, a gemstone miner headquartered in Dubai, was ordered by the ANM to suspend its Colombian mining operations after the company was found operating outside its concessions, according to local media.

The company had extended its underground tunnels into an adjacent property without holding a valid mining title.

In July 2022, Minerandes de Colombia S.A.S. was ordered by the ANM to suspend operations at its coal project in Nariño after inspectors found that its mine entrances lay outside of its registered concession boundary.[1]

The ANM’s translated order: “... it was identified that ALL work performed by MINERANDES DE COLOMBIA S.A.S. Under Concession Contract No. 7464, both the entrance to the mine entrances and the work fronts, since their granting to date, are located and carried out outside the area granted under the mining title (which appears to have been uninterrupted).” (Pgs. 7-8) ↩︎

Part 2: Collective Mining Is Operating In A Protected Forest Buffer Zone Where Mining Activity Is Not Permitted

Corporación Autónoma Regional de Caldas (“Corpocaldas”) oversees the use of natural resources in the region of Caldas. It is affiliated with the Colombian Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development.

Corpocaldas is responsible for issuing environmental licenses for the exploration and exploitation of natural resources under its jurisdiction, according to the entity's website.

Part Of Collective’s Drilling Activity At Its Apollo Target Is Over Riparian Forest Buffers, According To Data From Corpocaldas And Company Disclosures

Mining Activity Is Not Permitted On Riparian Forest Buffers, According To Corpocaldas

In March 2011, Corpocaldas issued a resolution that defined riparian forest buffers as areas adjacent to watercourses or springs where protective vegetation cover is necessary to safeguard renewable natural resources.

In these areas, exploration and mining are not permitted activities, according to the 2011 resolution.[1]

Article 6 of the March 2, 2011 resolution defines only 4 permitted uses of riparian forest buffers as: protective vegetation cover, erosion control works, crossing of roads and pipelines, and public utilities networks. This restriction only applies to subareas of a mining title, according to a local legal expert. ↩︎

Corpocaldas’ web platform allows the public to review the riparian forest buffer zones in the Caldas region, where Collective Mining operates.[1]

Using the methodology described in Appendix B, we found that many of Collective’s drill holes at Apollo appear to run directly through riparian forest buffers, as shown in the image below.

Further, some of Collective’s drill pads appear to have been constructed directly on top of Riparian forest buffers.

These findings indicate that Collective Mining is not only drilling in areas where it does not hold a mining title, as explained in Part 1, but it also appears to be drilling in environmentally-restricted areas.

Within The Last 30 Days, Two Of Collective’s Concession Applications Were Suspended Due To Environmental Concerns

In July 2025, the ANM issued orders suspending two of Collective Mining’s concession applications – #503983 and #505576.

The ANM order issued on July 8, 2025, regarding application #503983 stated that the requested area overlaps with an environmental zone where mining activity is not permitted.

The ANM suspended the application until Antioquia’s environmental authority clarifies if mining activities in the requested area are permitted, restricted or excluded after taking into account the presence of an environmental reserve. [1]

Application 503983 encompasses a total area located in two regions, Caldas and Antioquia, according to the ANM’s database. Corporación Autónoma Regional del Centro de Antioquia (“Corantioquia”) is the equivalent of Corpocaldas, for part of the region of Antioquia, according to Colombia’s Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development. (Pg. 6) ↩︎

The second ANM order issued on July 15, 2025 regarding application #505576 also stated that the requested area is located in an environmentally restricted area where mining activity is not permitted.

The ANM suspended this application until Collective provides the agency with information on the compatibility of mining activities with the environmental restrictions. [1]

Collective latest annual information form, does not name application 505576 filed on April 13, 2022, per the ANM. This annual information form, however, names application 505577 filed on April 13, 2022. (Pgs. 3, 8) ↩︎

Although the suspended concession applications are not associated with the Apollo target, these suspensions highlight the challenges of securing a mining title for zones that contain areas where mining activities are not permitted, such as riparian forest buffers.

Part 3: The Controversial Background Of Collective Mining’s Chairman

While Collective’s financial filings frequently reference its Chairman, Ari Sussman, and his team’s exit from Continental Gold to Zijin Mining, we found only one mention of his role at Colossus Minerals in Canadian filings and no mention in SEC filings. Colossus was a controversial gold mining company that operated in Brazil.[1]

We found only 1 result for Colossus when searching SEDAR: a filing statement dated May 12, 2021, which included Colossus in Sussman’s background. We confirmed our check with Bloomberg’s “CF” function which only yielded 1 result for Colossus. ↩︎

From February 2006 To October 2012, Collective’s Founder, Ari Sussman, Acted As Chairman And CEO Of Publicly Listed Colossus Minerals, Which Was Developing A Gold Mine With A Brazilian Mining Cooperative

From January 2010 To March 2011, Colossus Paid The Equivalent Of $11.7 Million To The Personal Account Of The Treasurer Of The Local Mining Cooperative, According To A Report Published By Local Media, Citing Investigations From Brazilian Authorities

In 2014, Colossus’ Mining License Was Cancelled By The Brazilian Congress: “The Entire Process, From The Outset, Was Riddled With Irregularities, Corruption, And Disregard For Our Country’s Laws,” Per A Brazilian Congressman Commenting On The Motivation To Cancel The Concession

Starting in February 2006, Collective’s founder and Chairman, Ari Sussman, acted as Chairman and CEO of Colossus Minerals Inc., according to company filings.

In 2007, Colossus Minerals partnered with a local mining cooperative that held the exploration license of the Serra Pelada Property, according to a company prospectus. [Pg. 7]

On May 7, 2010, the Brazilian Government signed the mining license for the Serra Pelada Project, according to a material change report filed by Colossus Minerals.

From January 2010 until March 2011, the treasurer of the local cooperative received the equivalent of $11.7 million in her personal account from Colossus Minerals, according to a report from Epoca, a magazine owned by local media conglomerate Globo.[1]

The report cited a money laundering investigation conducted by the Brazilian financial intelligence unit, COAF.

In 2012, Ari Sussman resigned from his role as Chairman of Colossus.

In 2014, the lower house of the Brazilian Congress cancelled the mining license granted for the Serra Pelada Project.

Among the alleged problems were Colossus increasing its stake in the project without the consent of the cooperative prospectors, as well as certain irregularities in Colossus’ financial transactions, according to an article from Agência Câmara Notícias, the lower house news agency.

A Brazilian congressman and member of the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (“PSDB”) Wandenkolk Gonçalves said:

"The entire process, from its inception, was riddled with aspects of irregularity, corruption, and disregard for our country's laws."

Colossus Minerals filed for creditor protection in 2014.

Conclusion: Collective Appears To Be Violating Basic Principles Of Mining Law At Its Flagship Apollo Target

Illegal mining has been a societal menace for decades in Colombia, leading to social unrest and environmental destruction. Aware of this, Collective has trumpeted its mission in helping local communities and asserted that it is “in compliance with all applicable environmental laws/and or regulations,” per its latest sustainability report.

Despite these proclamations, it is clear to us that Collective appears to have ignored the basics of mining law, drilling illegally at its flagship Apollo target, before obtaining the required mining titles— in disregard of Colombia’s law

Chairman Sussman states that he will “not settle for anything less than making another major discovery in Colombia,” per his X profile. Perhaps it is this drive that has pushed Collective to aggressive and unlawful exploration, which risks jeopardizing the future of its flagship mining target.

Appendix A: Identifying Collective Mining’s Activities And Its Mining Titles

To verify Collective’s mining activity and the titles associated with it, we used Google Earth Pro to overlay the company’s drill maps with the ANM’s mining title database.

Step 1: Locating Collective’s Mining Titles In Google Earth Pro

On the ANM mining title database, we searched for plots “LH0071-17” and “HI8-15231.” We then navigated to the “Panel Actions Menu” and exported each plot as a Shapefile (.shp).[1]

These files are ready to import to Google Earth Pro as is.

Step 2: Identifying Collective’s Apollo Target In Google Earth Pro

In Collective's April 2023 technical report, the company included a map showing hole traces and intersections at its Apollo target. From this map, we were able to identify at least two exact UTM coordinates intersections and 2 pads.[1]

Guayabales, region of Caldas is located in UTM Zone 18 N. The northern and first intersection we see in the map is Zone 18 N, Easting 431500, Northing 607500. The southern and second intersection we see in the map is Zone 18 N, Easting 431500, Northing 607000. The Collective map refers to “WGS84”, which is the same standard used by Google Maps. (Pg. 135) ↩︎

We took the two UTM coordinates provided by Collective and added placemarks on Google Earth Pro.[1]

In Google Earth Pro Preferences, ensure that the “Show Lat/Long Setting” is set to “Universal Transverse Mercator” and “Elevation Exaggertion” should be set at “0.01.” Before searching for the exact UTM coordinates, locate yourself in Marmato, Caldas in Google Earth Pro. ↩︎

We then overlaid the drill map onto Google Earth Pro, being sure to align the UTM coordinates from the map, while keeping its proportions. The topography from the map provided by Collective matched the topography seen in Google Earth Pro, further confirming the correct overlay of the maps.[1]

Navigate to “Add Image Overlay” on Google Earth Pro. Adjust the size of the overlay to match with the two Placemarks. Ensure the image is proportionate by holding the SHIFT key when adjusting the image size/placement. The topography of the maps can be confirmed by changing the opacity in the layers of the map. ↩︎

We were then able to identify the locations of Collective’s drill pads 2 and 3 at its Apollo target.

Step 3: Locating Collective’s Drilling Activities In Google Earth Pro

In a 2024 presentation, Collective published a scaled map with drilling results from its Apollo target. The presentation highlighted the location of drill pads 2 and 3.[1]

Zooming in on the presentation, one can see the locations of drill pads 2 and 3. [Slide 15]

Using the pad locations we ascertained in Step 2, we obtained the location of the Collective drilling activities on its Apollo target.

We overlaid the drilling results map with the mining title plots we exported from the ANM’s website in Step 1.

We found that a significant amount of Collective’s Apollo drilling activity is concentrated in areas without a mining title.

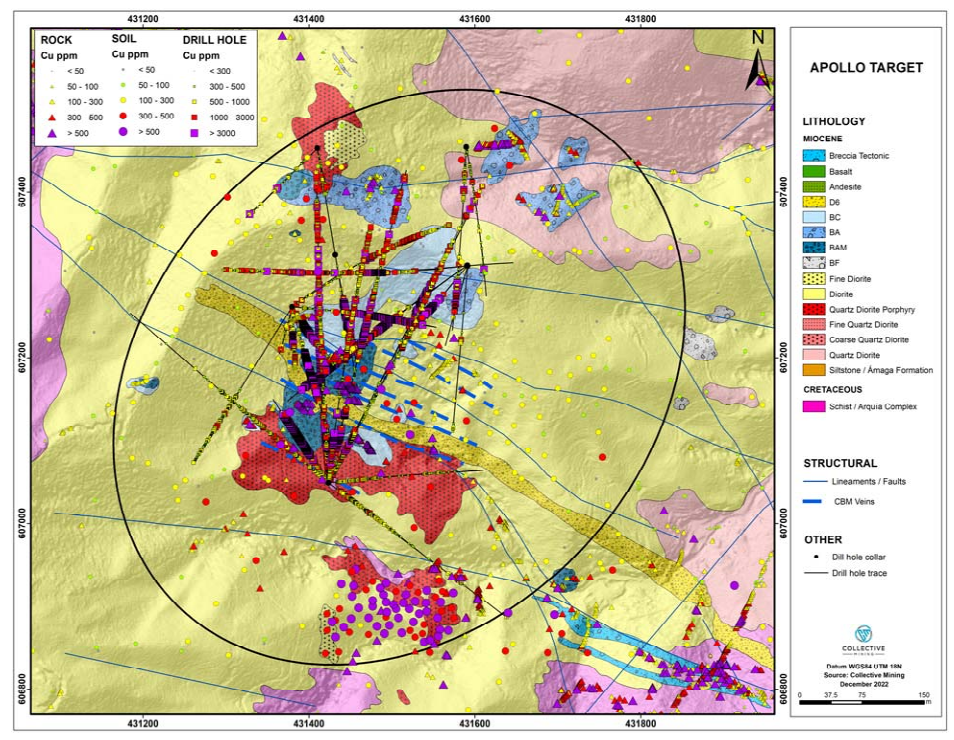

Corroboration Of Findings Using A Different Geological Map Of The Apollo Target Published By Collective Mining

We obtained the same results using another drilling map provided by Collective in its 2023 technical report, which also included UTM coordinates. [Pg. 93]

In this case, we had to manually create a grid to obtain the coordinates of 2 intersections.

As previously explained in Step 2, we then overlaid this map on Collective’s mining titles from the ANM database.

Following the same methodology, we used another map from the April 2023 technical report, which contains the location of 5 drill pads. [Pg. 63]

The overlay from that map provides further confirmation of Collective’s exploration activities, including the location of drilling pads, over areas without proper mining titles.

Appendix B: Identifying Riparian Forest Buffer Zones In The Guayabales Project

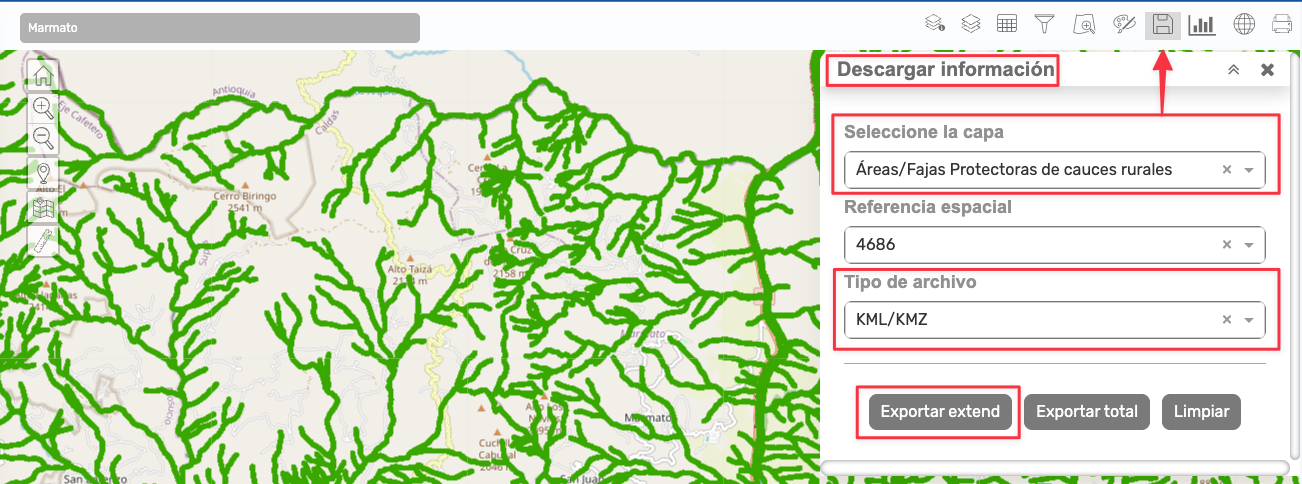

Using Corpocaldas’ map, we searched for Marmato. We then selected the layer “Áreas/fajas Protectoras De Cauces Rurales” listed under “Estructura Ecológica Principal.” This provides the location of the riparian forest buffers determined by Corpocaldas.

We then proceeded to download the layer in a KML/KMZ format from the Corpocaldas website.[1]

We opened the file in Google Earth Pro, which revealed the riparian forest buffers marked in white in the areas of Marmato and Guayabales.

Replicating the steps described in Appendix A, we overlaid Collective’s drilling activities on the riparian forest buffers map.

Disclosure: We are short shares of Collective Mining Ltd (TSX and NYSE American: CNL)

Legal Disclaimer

Use of Morpheus Research LLC’s (“Morpheus Research”) research is at your own risk. In no event should Morpheus Research or any affiliated party be liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information in this report. You further agree to do your own research and due diligence, consult your own financial, legal, and tax advisors before making any investment decision with respect to transacting in any securities covered herein. You should assume that as of the publication date of any short-biased report or letter, Morpheus Research (possibly along with or through our members, partners, affiliates, employees, and/or consultants) may have a position in the stock, bonds, derivatives, or securities covered herein and therefore stands to realize significant gains if the price of the securities move. Following publication of any report or letter, Morpheus Research intends to continue transacting in the securities covered therein and may be long, short, or neutral at any time thereafter regardless of Morpheus Research’s initial position or views. Morpheus Research’s investments are subject to its risk management guidance, which may result in the de-risking of some or all its positions at any time following publication of any report or letter depending on security-specific, market or other relevant conditions. This is neither an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security, nor shall any security be offered or sold to any person, in any jurisdiction in which such offer would be unlawful under the securities laws of such jurisdiction. Morpheus Research is neither registered as an investment advisor in the United States, nor does it have similar registration in any other jurisdiction. To the best of Morpheus Research’s ability and belief, all information contained herein is accurate and reliable and has been obtained from public sources believed to be accurate and reliable, and who are not insiders or connected persons of the stock covered herein or who may otherwise owe any fiduciary duty or duty of confidentiality to the issuer. Conclusions expressed herein are based upon the information disclosed herein and represent the opinion of Morpheus Research. Such information is presented “as is,” without warranty of any kind – whether express or implied. Morpheus Research makes no representation, express or implied, as to the accuracy, timeliness, or completeness of any such information or with regard to the results to be obtained from its use. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice, and Morpheus Research does not undertake to update or supplement this report or any of the information contained herein.